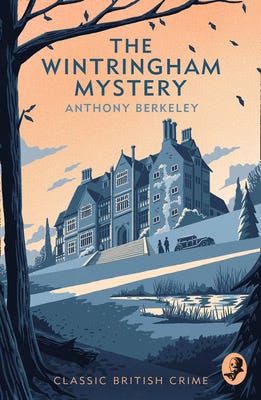

The Wintringham Mystery by Anthony Berkeley

A puzzle mystery so devilishly difficult no reader could solve it - not even Dame Agatha

I first read The Wintringham Mystery years ago, and finished my reread way back in February. I planned to write about it once I finished up my ski-themed posts in March, but time got away from me. I took an unexpected hiatus for personal reasons, but I’m hoping to get back to my usual-ish posting schedule. Thanks for sticking around, and if you’re new to The Butler Did It, welcome!

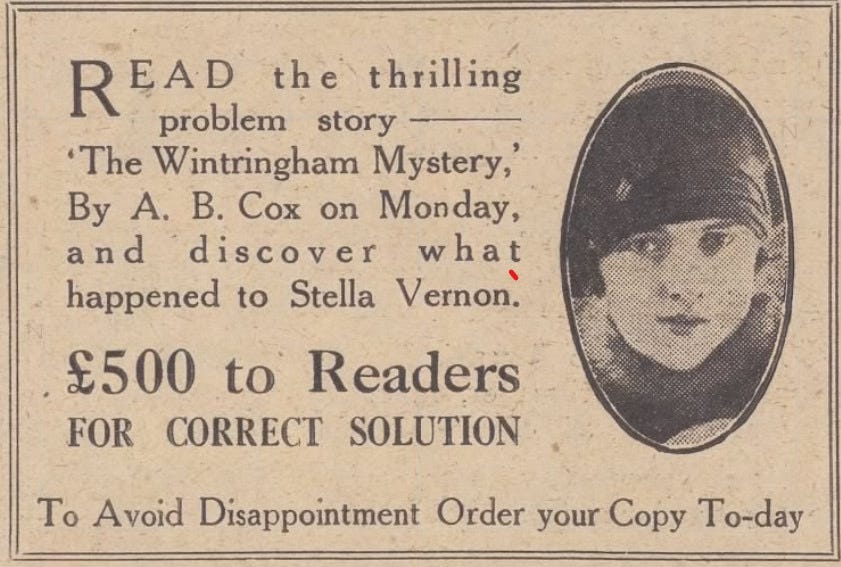

Is there a more charming a Golden Age writer than Anthony Berkeley? The introduction of our amateur detective in The Wintringham Mystery, originally published as a serial in The Daily Mirror in 1926 (Readers were left on a cliffhanger and were invited to solve the puzzle for a prize. No one, including Agatha Christie, succeeded.) makes me think not:

Bridger, confidential valet to Stephen Munro, Esq., of 196B Half Moon Street, was a man of singularly equable temperament. Even the fact that he laboured under the first name of Ebenezer, which is enough to upset anyone, did not appear to cause Mr. Bridger any sleepless nights; he bore the burden with the same calm stoicism with which he had carried out his duties for the last eight years as servitor to Mr Stephen Munro, both as batman in France and as general valet-housemaid-private-secretary in the more strenuous times of peace. Bridger was forty-two to his master’s twenty-seven, and life held no further disillusions for him.

This was fortunate, because Stephen Munro, eating the admirable kidneys and imbibing the faultless coffee which Bridger had prepared, was meditating the disclosure of a piece of news which to anybody not so fortuitously equipped would have been less of a disillusionment than a plain cataclysm.

He drew his purple dressing-gown a little more closely round his tall, lithe, athletic frame and leaned back in his chair. “There’s one thing I will say for you, Bridger,” he remarked with the contented sigh of the delectably fed, “you can cook kidneys.”

“Yes, sir,” Bridger agreed stolidly, preferring his employer a heavy silver box. “Cigarette, sir?”

“Thanks.” Stephen extracted one from the box and applied it to the match which Bridger was now holding out to him. He inhaled a couple of deep mouthfuls of smoke, and began to stroke the hair on the left side of his head with a gesture that was habitual to him. Stephen’s hair was inclined to be distinctly curly, and though this had delighted the heart of his mother, Stephen himself regarded it in the light of an affliction; as a small child he had thought that assiduous stroking movements must succeed eventually in smoothing it out, and though, like Bridger, life held few more illusions for him, the habit persisted.

“Bridger,” observed Stephen with the utmost cheerfulness, still mechanically smoothing the unsmoothable. “Bridger, I’m afraid I’ve got a bit of a shock for you.”

Stephen is broke, having frittered away his inheritance on his life of leisure, and as a result has taken a job as a footman for Lady Susan at her home in the country. It doesn’t last long: he is simultaneously fired and invited to stay on as a houseguest two days into his tenure by the tough-on-the-outside-marshmallow-inside Lady Susan. (If you’re looking for an insightful and thought-provoking treatise on class inequality, this is assuredly not that book.)

Naturally there is a house party at Lady Susan’s estate and equally naturally, his good pal Freddy and his love interest, Pauline, are guests. So far, so fun. Stephen butts heads with Martin, the butler, before reverting to his native class status, and I am pleased to say that the butler features prominently in his story, even though he is something of an antagonist.

In his brief foray as footman, Stephen is called on to participate in a bit of friendly witchcraft after dinner one evening. During the seance Lady Susan’s niece, Cecily, disappears. When she hasn’t turned up the following morning, Stephen and Pauline begin to investigate. They uncover guests with ulterior motives, a secret passageway, and suspicious servants: in short, all of the ingredients for a classic good time.

Spoilers from this point on!

Dame Agatha can be forgiven for not correctly deducing the solution to the story, as it involves the villain of the piece accidentally killing himself in a trap he set for someone else. It gives me great pleasure to announce that in this case, the butler did, in fact, do it (although the it is kidnapping, not murder). In the hopes of scaring Lady Susan to death (she has a weak heart and he has secretly married her niece and will therefore inherit) Martin hides in the background making spooky noises during the seance and, when that doesn’t work, kidnaps Cecily until he can try again. Stephen is onto him, so Martin sets a very unlikely trap, but it springs too early, killing him in the process. It’s a convoluted conclusion, and, if I’m honest, a somewhat disappointing one. Martin dies halfway through the novel (his accomplice carries on with their plans), rendering the reveal in the final pages anticlimactic.

Equally disappointing is Berkeley’s handling of Bridger, introduced as a potential Watson to Stephen’s Holmes (or Jeeves to his Wooster). He is sidelined for the majority of the book so Stephen and Pauline can investigate together. Pauline is fine — she’s a playful and plucky heroine of the typical Golden Age mode, but Bridger feels like a lost opportunity for some deadpan humor.

Though Stephen’s domestic service career is short-lived, Berkeley’s inclusion of the downstairs is typically novel — he was constantly looking for ways to stretch and twist the conventions of the genre, and giving his hero a first-hand taste of the difficulty of working in a great house is certainly unique. But making the butler the culprit is more unusual than the cliché (obviously embraced by this Substack) would suggest.

There are a few short stories prior to 1926 featuring guilty butlers (the most well-know of which is the Sherlock Holmes short story “The Adventure of the Musgrave Ritual” in 1893), but S. S. Van Dine’s famous list of rules for detective fiction, which included a “no servants must be guilty of the crime” line wasn’t published until 1928 and the phrase “The butler did it” wasn’t popularized in fiction until 1930’s The Door by Mary Roberts Rinehart. Berkeley seems to be ahead of the curve here, although this work is rarely recognized as a forerunner of the cliché, perhaps because of Martin’s early accidental death. Still, it’s a pleasure for this Butler to say, for once: The Butler Did It.

Further reading: Berkeley published a total of twenty-four books (some under the pseudonym Francis Iles), including ten featuring amateur detective Roger Sheringham, famous for his fallibility. The most well known of these is The Poisoned Chocolates Case, which features multiple possible solutions (but only one that is correct).

Further listening: The Sheddunit podcast has an excellent episode exploring why the phrase “The Butler Did It” has resonated in spite of so few fictional examples.

Read with me! I publish on Tuesdays, alternating between short stories and novels.

Next week: “The Fordwych Castle Mystery” by Baroness Orczy

In two weeks: Cat and Mouse by Christianna Brand