“I have a passion for detective stories. Of beer an enthusiast has said that it could never be bad, but that some brands might be better than others; in the same spirit (if I may use the word) I approach every new detective story.”

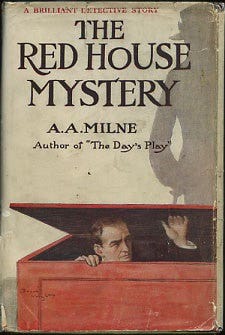

From A. A. Milne’s 1926 introduction to The Red House Mystery (originally published in 1922) and henceforth The Butler Did It’s motto

In an introduction written after the initial publication of The Red House Mystery, Milne lays out his rules for the detective genre. He is anti-specialized knowledge and anti-romance: “A reader, all agog to know whether the white substance on the muffins was arsenic or face-powder, cannot be held up while Roland clasps Angela’s hand ‘a moment longer than the customary usages of society dictate’…By all means let Roland have a book to himself in which he can clasp anything he likes, but in a detective story he must attend strictly to business.”

Of the Watson, the character designed to act as support and sounding board to the detective, Milne says, “Death to the author who keeps his unravelling for the last chapter making all the other chapters but prologue to a five-minute drama. This is no way to write a story. Let us know from chapter to chapter what the detective is thinking. For this he must watsonize or soliloquize; the one is merely a dialogue form of the other, and, by that, more readable. A Watson, then, but not of necessity a fool of a Watson. A little slow, let him be, as so many of us are, but friendly, human, likable…”

And so there is a Watson in The Red House Mystery. The plot is a genre classic: the body of a man is found alone in the locked office of a house owned by Mark Ablett, who is now missing. What happened in the locked room, and where is Mark? Amateur detective Anthony Gillingham happens upon the scene and takes it upon himself to investigate, enlisting his friend Bill Beverly to play Watson to his Holmes.

Beverly’s Watson is - and this is important in setting the playful tone of the novel - an enthusiastic participant in the investigation. It’s a rare take on the Watson, and one with which readers instinctively identify. What inveterate reader of detective fiction has not longed to take part in an investigation of their own?

“What fun!” Beverly exclaims when his friend decides to play detective, like a child being taken on an outing to the zoo rather than an adult man hot on the trail of a cold-blooded killer. It’s this tone that makes the book such a delightful read, and Beverly is integral to maintaining it. He’s always game, ready to make himself “pleasant to the landlady” (prurient minds want details!) or take off on a wild goose chase through the local pubs in search of a phantom guest.

He is always a step behind Gillingham, as a good Watson must be, but like Conan Doyle’s Watson, who was not such a buffoon as some film and television adaptations depict him to be, he is an able second. No mere note taker (sorry, Hastings), Beverly proves his usefulness when recovering a clue from the bottom of a lake, diving again and again into he cold, dark water until he retrieves the sunken box. He thinks on his feet when Gillingham is exploring the secret passage and Cayley suddenly appears, tapping out a message in Morse code to alert his friend.

Yet like all Watsons, he is lesser than. He must be told repeatedly to stop discussing the case within earshot of one of the major players. He fails to grasp the significance of the secret passageway until it is pointed out to him. With his shortcomings, he represents us mere mortals, provided with the same information as the genius detective and coming up lamentably short. Much as we like to pretend we would be the detective hero of the novel, if we are honest with ourselves, we know that we are all, alas, the Watson, plodding along with only our unflagging faith in the genius of our Holmes to guide us. I am Watson; Watson is me.

When the Watson is as affable as Bill Beverly, that doesn’t seem too bad. His best trait is his amiability but amiability is nothing to sneeze at, especially in a Watson. A bickering Holmes and Watson can take a sharp left away from entertaining toward hostility. Alternatively, witty repartee is hard to come by when your Watson is as dull as dishwater. It’s a fine line to walk, and more difficult to pull off than it may seem. A too-dim Watson is tiresome; a too-clever Watson superfluous. He is an everyman in intelligence and ability, but must be unique enough to hold our attention. Nothing is more insulting than a boring reader surrogate.

Watsons often provide the moral counterpoint to their taciturn and unfeeling detectives. Gillingham semi-apologetically justifies his analytical take by noting that he had never before met the victim or suspect, leaving it to Beverly to express his discomfort when suspecting a friend of being involved in the murder: “Cayley was just an ordinary man - like himself. Bill had had little jokes with him sometimes; not that Cayley was much of a hand at joking. Bill had helped him to sausages, played tennis with him, borrowed his tobacco, lent him a putter…” In contrast to Gillingham’s ‘just the facts’ Holmes, Beverly alone seems to grasp the emotional stakes of suspecting those around you, however fleetingly.

Ultimately, a Watson is part of a duo, and it is the relationship between him and Holmes that leads their narrative to become either an instant classic or sad throwaway in the remainder bin. Here Milne shines. Gillingham and Beverly are very much representatives of their type - wealthy young gentlemen with the leisure time to dedicate to solving a mystery - but they are charming examples. The pleasure they take in each other and in the mystery they unravel is contagious, and the reader is swept along in the enthusiasm of two pals having a lark. When Milne writes that Beverly greatly admires Gillingham, we believe him. When Gillingham compliments Beverly as “the most perfect Watson that ever lived,” well, we can only nod our heads in agreement.

It’s a shame Milne never made good on the promise implied at the end of the book:

“The Barringtons,” he said. “Large party?”

“Fairly, I think.”

Anthony smiled at his friend.

“Yes. Well, if any of ‘em should happen to be murdered, you might send for me. I’m just getting into the swing of it.”

Further reading: Milne, who was more interesting than the Disney-fied legacy of Winnie the Pooh suggests, is the subject of A. A. Milne: The Man Behind Winnie-the-Pooh (1990) by Ann Thwaite.

Raymond Chandler’s essay “The Simple Art of Murder” famously takes on the merits of the detective novel, singling out The Red House Mystery as a (negative) example of the genre and arguing that its solution is impossible. This may be technically correct but is pretty rich coming from the author of The Big Sleep, which famously never solves its inciting disappearance at all.*

*Yes, I know that isn’t he point he’s making in the essay, and I love Chandler too, but come on.