Despite the predominance of female authors in Golden Age detective fiction, the genre tends not to be the feminist utopia one wishes it were. After all, almost anything written over one hundred years ago is going to bear the mark of its time. Even the most progressive authors were only progressive for their era. It’s easy to call them out now rather than to remember that female novelists were walking a delicate high wire act between their personal and professional lives.

Whatever expectations modern readers have of female Golden Age authors, they gave us indelible female sleuths: Miss Marple, Mrs. Bradley, Miss Silver and Harriet Vane (not technically a detective, but she is the main character in Sayers’ masterpiece, Gaudy Night) to name but a few. These are all complex characters, full of contradictions and depth. And then there is Lady Molly.

Lady Molly of Scotland Yard is a collection of twelve short stories featuring the titular detective. Written by Baroness Orczy in 1910, Lady Molly occupies a place in detective history as the first female Scotland Yard detective (predating the real thing by at least a decade). At first glance, she seems like a feminist dream: a female professional detective with a female sidekick, written by a woman, solving mysteries at a time when women, particularly of her social class, were confined to the home. But as even the most casual Google search will tell you, modern readers hate Lady Molly.

The collection starts off promisingly enough, with Mary, Lady Molly’s Watson-figure and narrator jumping right in:

Do you suppose for a moment, for instance, that the truth about that extraordinary case at Ninescore would ever have come to light if the men alone had had the handling of it? Would any man have taken so bold a risk as Lady Molly did when—— But I am anticipating.

Let me go back to that memorable morning when she came into my room in a wild state of agitation.

“The chief says I may go down to Ninescore if I like, Mary,” she said in a voice all a-quiver with excitement.

“You!” I ejaculated. “What for?”

“What for—what for?” she repeated eagerly. “Mary, don’t you understand? It is the chance I have been waiting for—the chance of a lifetime? They are all desperate about the case up at the Yard; the public is furious, and columns of sarcastic letters appear in the daily press. None of our men know what to do; they are at their wits’ end, and so this morning I went to the chief——”

“Yes?” I queried eagerly, for she had suddenly ceased speaking.

“Well, never mind now how I did it—I will tell you all about it on the way, for we have just got time to catch the 11 a.m. down to Canterbury. The chief says I may go, and that I may take whom I like with me. He suggested one of the men, but somehow I feel that this is woman’s work, and I’d rather have you, Mary, than anyone.

Unfortunately, that’s as nice as Lady Molly will be to poor Mary for the rest of the book. It’s a straight shot downhill from there, with almost every story inducing an aggressive eye roll or worse. The relationship between Lady Molly and Mary is not one of equals, or even mentor/protege. It is master and servant, with Lady Molly treating Mary as a prize idiot not deserving her respect, and Mary full-on hero worshipping Lady Molly in response.

Worse than Lady Molly’s treatment of her companion is her method of detection, which often involves lying to suspects to trick them into confessing, stealing evidence for her own use and generally skirting the law she is bound to uphold. The mysteries in this collection are not puzzles that are possible for the reader to solve; indeed, it is a mystery how Lady Molly does it, besides her much-touted “feminine intuition.” In spite of her hit rate, Lady Molly is a terrible detective.

Spoilers below for “The Fordwych Castle Mystery”

There are essentially no men in “The Fordwych Castle Mystery,” as Mary herself points out when Lady Molly is assigned to the case. This would seem to be an opportunity for the women to shine, but in Orczy’s hands it is an opportunity for woman on woman violence. The story centers around a baroness who takes in her deceased sister’s eldest daughter, Henriette. When Henriette’s father dies, her younger sister, Joan, joins them:

From all accounts, the first hint of trouble in that gorgeous home was coincident with the arrival at Fordwych of a young, very pretty girl visitor, who was attended by her maid, a half-caste woman, dark-complexioned and surly of temper, but obviously of dog-like devotion towards her young mistress.”

I wish I could say it got better from there, but it assuredly does not. The maid, Roonah, is violently murdered in her room, and the narrative has so little use for her other than to advance the story with her death, that Orczy never takes the time to develop her character aside from a few more racist descriptions. Murder victims in Golden Age fiction are often a means to an end more than anything else, but being a plot device is a lot more palatable when the victim is a rich white man. Roonah is as ill-used by the story as her character is by her mistress, Joan.

Joan is portrayed as all sweetness and light while her sister, Henriette, is haughty and uncaring.

Henriette, on the other hand, looked distinctly bored. Once or twice she had yawned audibly, which caused quite a feeling of anger against her among the spectators. Such callousness in the midst of so mysterious a tragedy, and when her own sister was obviously in such deep sorrow, impressed everyone very unfavourably. It was well known that the young lady had had a fencing lesson just before the inquest in the room immediately below that where Roonah lay dead, and that within an hour of the discovery of the tragedy she was calmly playing golf.

Henriette is not the killer, of course (that honor goes to her sister, Joan) but she is horrible. They all are, including Lady Molly.

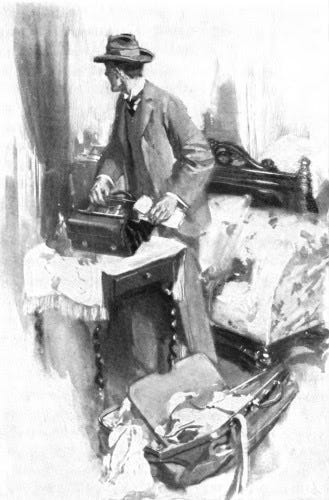

Lady Molly detains her suspect, Joan Duplessis, while an associate searches her room, “with orders to break open the locks of her hand-bag and dressing-case.” Lady Mary finds the incriminating evidence (papers forged in an attempt to prove her sister’s illegitimacy and therefore inherit her aunt’s fortune), but how she knew they were there, and how she gets away with what is essentially breaking and entering is a question only the Baroness can answer. Lady Molly is above the law.

Perpetrators occasionally jump out of windows or in front of trains when faced with Lady Molly’s assaults on justice, and I can’t say I blame them.

Further reading

Lady Molly of Scotland Yard is in the public domain and available through Project Gutenberg, should you be so inclined, although I don’t recommend it.

Murder in the Links

Looking for something a little more fun than Lady Molly’s extrajudicial form of justice? Try one of these!

Stephen Fry on the greatness of P. G. Wodehouse