On G.K. Chesterton, Father Brown and the Pleasure of the Deeply Uncool

Some thoughts on the enduring popularity of the Father Brown mysteries

Golden Age detective fiction is not cool. Eternally popular, deeply beloved (by me!), endlessly adaptable and constantly rediscovered by new generations of readers, yes. Agatha Christie is outsold only by the Bible,1 contemporaries as varied as Rian Johnson and Ruth Ware2 are inspired by Golden Age tropes, but the cool lit girls with their Sally Rooney tote bags are not, as a rule, filling them with Margery Allingham and Dorothy L. Sayers.

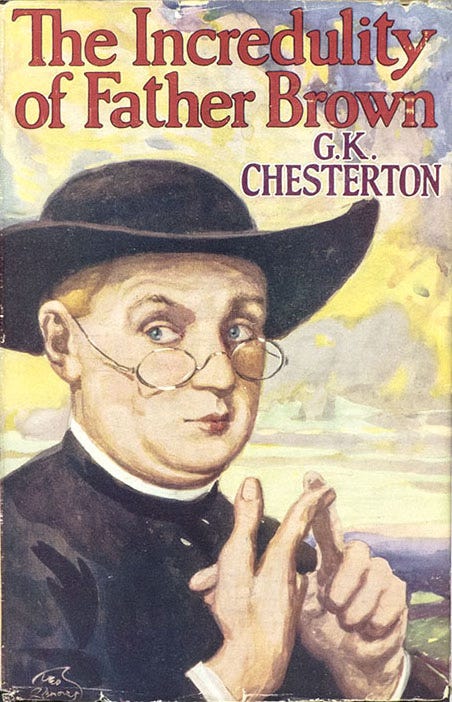

Perhaps no Golden Age author is as uncool in the contemporary sense as G. K. Chesterton. His most enduring legacy is Father Brown, who featured in 53 (!) short stories between 1910 and 1936. In a genre full of parsons and vicars, Father Brown is a Roman Catholic priest, a vocation that is (no offense to Catholics) deeply uncool. Catholicism’s closest brush with cool was when the Kennedys made it briefly, if erroneously, glamorous, but Catholicism today is plagued by scandal and an out of touch, misogynistic worldview.

So why does Father Brown, described by Chesterton in the short story “The Hammer of God as “not an interesting man to look at, having stubbly brown hair and a round and stolid face,” remain so popular today? He’s not handsome or witty, not dashing or adventurous. Upon pinpointing the criminal, he is apt to take him aside for a talk, as he does in “The Hammer of God,” and encourage him to confess his sins.

*Spoilers ahead*

In that story, two brothers, one a playboy and scoundrel, the other a deeply religious Anglican curate, meet on the street one morning. The former goes off to seduce a local married woman, the latter to church to pray. The playboy is killed, seemingly impossibly, his skull crushed by a small hammer. Only Father Brown deduces the solution - that the curate has murdered his brother by throwing the hammer from the top of the church.

Father Brown is fascinating in that his priesthood, rather than isolate him from the base thoughts and feelings of man, provides a deeper connection to them. It is through listening to the confessions of sinners that he understands man’s capacity for evil, enabling him to solve crimes.

Father Brown is also an underdog, a Roman Catholic in a country of Anglicans. Chesterton, who produced mountains of writing during his lifetime, including poems, plays and articles, was an outspoken defender of the underdog and the underpriviledged. What mattered to him was “knowledge of man and society.”3 Religion for Father Brown is about compassion and forgiveness, through which redemption is possible. In “The Hammer of God,” Reverend Bohun, the religious brother, loses sight of this, looking down (literally) on his fellow man.

Chesterton portrays Reverend Bohun as confused by the great height of the church into believing he had the authority of God to choose who deserves life and who death. A description of the gothic architecture of the church edifice as offering a “topsy-turvy” view of the world melds with a larger statement about the dizzying heights offered by a religiosity cut off from human compassion. (source)

It’s the humanity, the generosity of spirit, that people respond to in Father Brown stories today. Other Golden Age mystery writers are cleverer, wittier, more fun to read, but at their heart they are often about the puzzle, not the person (the best are about both). Father Brown offers something different: character-driven crimes motivated by human passions, a focus on man’s responsibility to man, and the possibility of redemption.

All of which is a long-winded way of saying: go read some Chesterton, why don’t you? Start with “The Hammer of God,” the first Father Brown story and one that distills several characteristics of the series down to their essentials: temptation, redemption, and man’s capacity for evil.

If you want more Father Brown: Check out Mark Williams’s iconic portrayal in the popular television series, currently filming its 14th season. This article provides a great overview of Chesterton and his most enduring creation.

is this still true? It feels true.

both very cool people!

The Life of Crime: Detecting the History of Mysteries and Their Creators by Martin Edwards